LINDHOLME HALL ESTATEA Place of Enduring Heritage

Tucked within the vast and ancient Humberhead Peatlands, Lindholme Hall Estate is a landscape unlike any other. Formed by ice and shaped by water, this rare calcareous island has borne witness to layers of human and ecological history—from a 5,000-year-old Neolithic trackway to centuries as a place of refuge and contemplation.

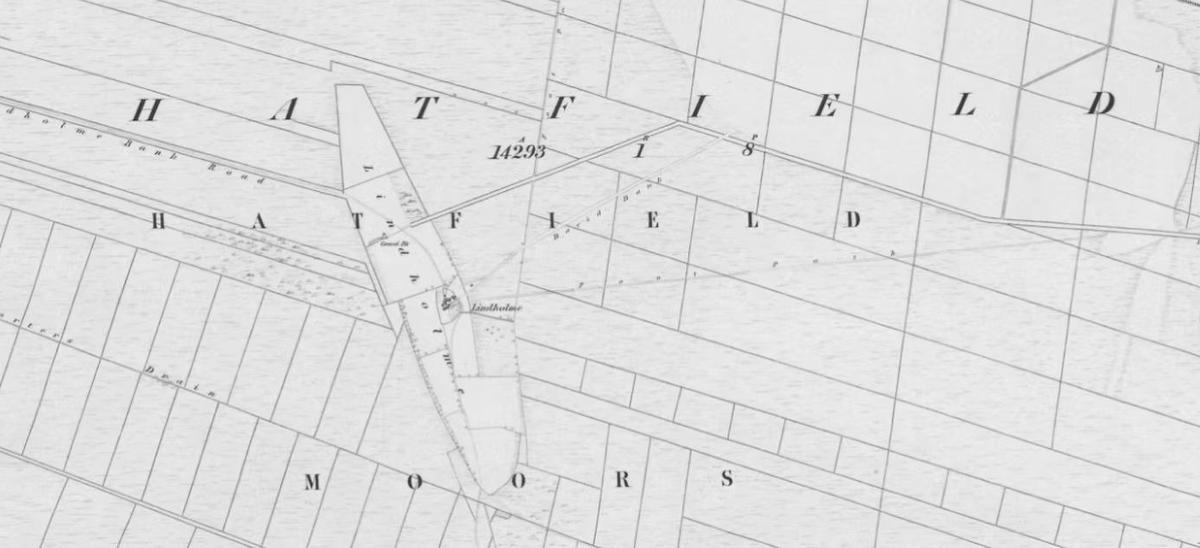

Lindholme Hall Estate, situated in the centre of Hatfield Moors and surrounded by the Humberhead Peatlands National Nature Reserve in South Yorkshire, England, is a living tapestry of geological wonder, ecological richness, and spiritual refuge—a rare and remarkable legacy to protect and share. About

Geological Formation

Lindholme Island was formed from the sands and gravels deposited during the last Ice Age, around 20,000 years ago, when the now-vanished Lake Humber covered nearly 20% of what is now England. As glaciers retreated and catastrophic flooding drained the lake through the Humber estuary, Lindholme emerged as a gravel-capped island in a vast tidal wetland.

Over the following millennia, surrounding peatlands developed into what is now the Humberhead Peatlands National Nature Reserve—a habitat of international ecological significance. Lindholme, uniquely, stands as a calcareous island within acidic peat, supporting rare flora, fauna, and complex soil systems. It is both a geological and ecological treasure.

This liminal, ever-changing landscape—once a tidal estuary—has long offered natural seclusion and a sense of otherworldly depth.

Neolithic Footsteps

In 2004, a remarkable archaeological discovery confirmed Lindholme’s prehistoric importance: a Neolithic timber trackway, preserved deep within the peat and radiocarbon-dated to over 5,000 years ago (±50 years), was unearthed on the edge of the island. Now a Scheduled Ancient Monument, it is one of the oldest engineered trackways in Europe.

A polished stone axe head was also discovered along the line of the trackway. This artefact, now housed in Doncaster Museum, stands as a key piece of evidence for prehistoric activity across the region.

One compelling theory suggests the track formed part of a long-distance trade and pilgrimage route, linking the flint quarries of the Vale of York with what is now continental Europe—at a time when sea levels were significantly lower. This aligns with wider patterns of ritual movement and cultural exchange in prehistoric Britain.

Anglo-Saxon Echoes

As centuries passed, Lindholme’s identity as a sacred place continued—possibly even connected to the lost Anglo-Saxon monastery of Donemutha (“Mouth of the Don”). Mentioned in a letter from Pope Paul I (c. 757–758 AD) and later in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Donemutha was reportedly destroyed by Viking raiders in 794 AD.

Although long associated with Jarrow, recent scholarship places Donemutha more plausibly in the Lower Don Valley—precisely the landscape in which Lindholme lies. While no definitive link has yet been proven, Lindholme’s proximity to the key waterways described in early sources, along with its enduring spiritual associations and seclusion, makes it a compelling location. The mystery remains open, inviting future exploration.

Remains of a Medieval Chapel

While the monastery of Donemutha remains a mystery, more tangible traces of Christian presence appear in the 17th and 18th centuries.Several historical sources describe remains of an ancient chapel, a stone-paved floor, and a constructed causeway—evidence that led antiquarians such as Rev. Abraham de la Pryme to propose that the site was a pre-Conquest religious settlement. Later researchers, including M.E. Oliver and Martin Limbert, have supported this view based on both physical traces and historical accounts.

“My opinion is that this was in former times before William ye Conqueror’s days, a religious place, and that it was destroyd by some invasion’s of ye Dain’s... ye loneliness and solitariness of this place renders it fit for such a purpose, for all ye religious houses formerly were built in such places...I doubt not at all but that this has been a religious place.”

Rev. Abraham de la Pryme, c. 1700, quoted in Lindholme: An Outline History by M.E. Oliver

The Heritage of William de Lindholme

One of the most enduring legends associated with Lindholme is that of William of Lindholme—a hermit said to have lived in solitude on the island in the 15th century. Part of local folklore for generations, his story blends historical record with oral tradition. In 1727, antiquarian George Stovin, accompanied by Reverend Samuel Wesley, visited the site and documented a grave beneath a freestone slab, accompanied by a skull, large bones, hemp seed, and a copper token.

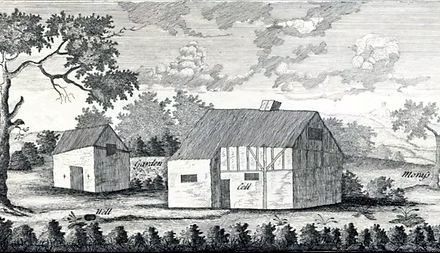

They also described the remains of a hermitage, with an altar at the east end and a clear spring nearby—an especially rare feature in the surrounding peatland. Engravings from the time depict a chapel-like structure surrounded by stillness, reinforcing the impression of Lindholme as a place of quiet retreat.

“The people of Hatfield and places adjacent have a tradition, that on the middle of Hatfield Waste there formerly liv’d an antient Hermit who was called William of Lindholme… At the east end stood an alter made of hewn stone and at the west is the Hermit’s grave cover’d with a free stone that measures in length 8 foot and a half, in breadth 3, and in thickness 8 [inches].”

George Stovin, Letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine, 1727

The mile-long stone causeway linking Lindholme to the nearby village of Hatfield helped preserve its sacred seclusion, with access shaped by both geography and season—a quiet isolation that would continue to define Lindholme as a place of refuge.Ecological Wonder

Lindholme’s sacred heritage is inseparable from its natural setting. The surrounding Hatfield Moors remain one of the UK’s most ecologically significant peatlands—a wild, waterlogged, and elemental landscape as rare and fragile as any patch of the Amazon Rainforest. It preserves not only specialised flora and fauna adapted to these conditions, but also an atmosphere of extraordinary stillness.

For centuries, this landscape has protected Lindholme’s seclusion—shaping its role as a sanctuary of contemplation, renewal, and connection with nature.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, writers and visitors described Lindholme as a place of solitude and mystery. Stonehouse (1839) and Pontefract & Hartley (1939) both noted its spiritual atmosphere. Even as industrial change swept across the region, Lindholme remained a sanctuary—held in memory, nature, and community.

Recognising this unique legacy, Gomde UK has been actively working to restore parts of the landscape degraded by centuries of drainage and industrial peat extraction—reviving the delicate balance of the raised bog ecosystem and renewing its capacity to support biodiversity, carbon storage, and climate resilience. This work continues Lindholme’s deep tradition of care, linking past and present through ecological stewardship.

Explore Our Environmental Conservation Efforts

A Living Legacy

Though centuries have passed, Lindholme’s sense of place and purpose endures.A refuge of peace, contemplation, and ecological wonder, Lindholme Hall remains a nurturing sanctuary where nature thrives and Britain’s lesser-known sacred history lives on—welcoming new generations into a deep and living heritage.